How to Write an Introduction in a Dissertation: A Clear, Step-by-Step Guide

The introduction chapter carries a lot of weight. It is the first sustained contact your reader has with the study and it must do three jobs at once: orient the reader, justify why the study matters, and define exactly what the study will accomplish. If you came here wondering how to write an introduction in a dissertation, this guide walks you through the essential parts in a teaching tone, with simple step-by-step prompts you can follow. The focus is only on the introduction chapter. No lines, no fluff, just practical structure and examples students can apply today.

Discover our complete dissertation guide series: [Abstract], [Introduction], [Literature Review], [Methodology], [Results], [Conclusion], [Discussion], [References], and [Appendix].

What the Introduction Chapter Must Deliver

A strong introduction answers four questions with clarity and confidence. What is the topic. Why is it important. What precise problem or gap does it address. What the study aims to achieve and how that aim translates into objectives and guiding questions or hypotheses. Everything in this chapter should point toward those answers, without turning into a full literature review or a methodology chapter.

Length and Timing

For most programmes the introduction is about 10 to 15 percent of the dissertation. A master’s project of 15,000 words usually has an introduction of roughly 1,500 to 2,000 words. A doctoral thesis will be longer. Write a solid working version early so your research stays focused, then revise it near the end so terminology, aims, and questions match the final study.

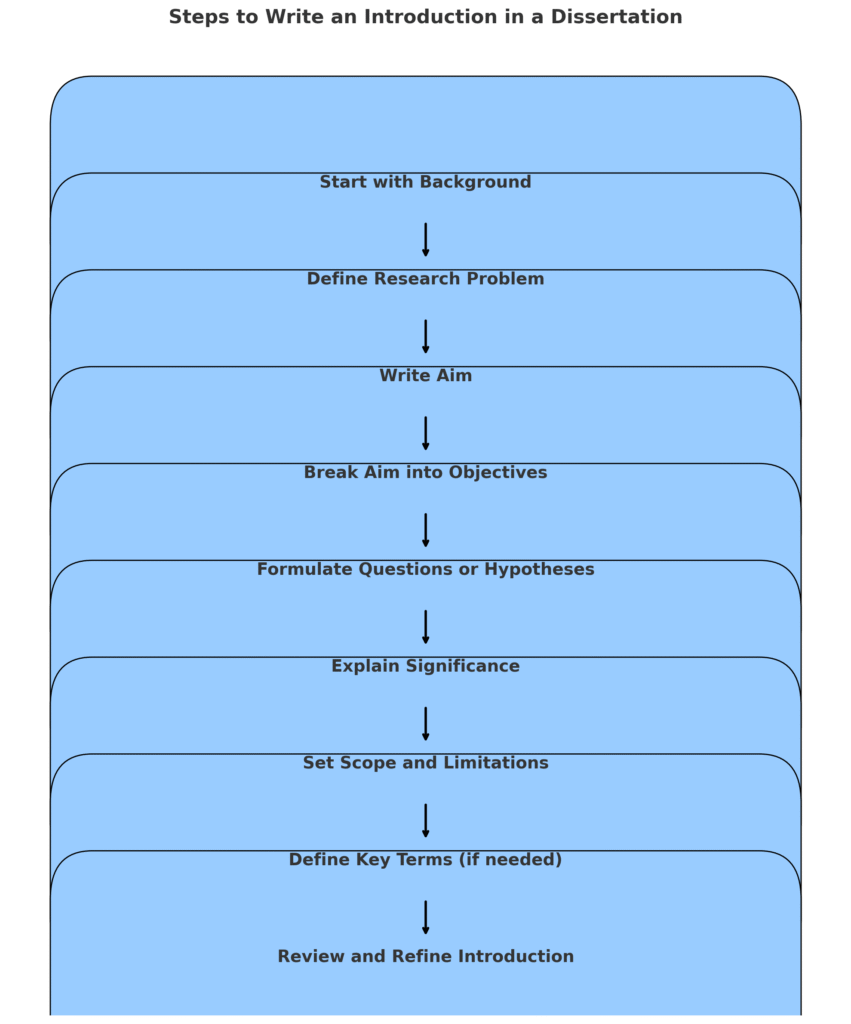

Core Components at a Glance

- Background of the study that orients the reader without becoming a literature review

- Problem statement that isolates the precise gap or issue

- Aim and objectives that define what the study will accomplish

- Research questions or hypotheses that guide the investigation

- Significance that explains why the study matters academically and practically

- Scope and limitations that set realistic boundaries

- Definition of key terms where needed for clarity

Step by Step: Build Each Part of the Introduction

Step 1. Write a focused background

Open with a short context that helps the reader see the big picture before you narrow to the specific problem.

Do this

- Name the broad topic and why it matters right now

- Identify two or three high-level trends or debates in the field

- Indicate the specific context you will focus on, such as a population, sector, or country

Keep it tight

- One to three paragraphs is usually enough

- Avoid detailed study-by-study summaries that belong in the literature review

Sentence starters you can adapt

- Recent developments in [field] have highlighted [issue], raising questions about [specific area].

- Although interest in [topic] has grown, there remains limited clarity about [focus].

- In [context], stakeholders face [challenge], suggesting a need to investigate [focus].

Step 2. State the research problem

This is the heart of the introduction. It explains what is missing, unclear, or conflicting in current knowledge or practice.

Three moves

- What we know: briefly summarise the current state of understanding

- What we do not know: specify the gap, inconsistency, or constraint

- Why it matters: show the consequence of that gap for theory, policy, or practice

Compact template

- Despite [what we know], there is limited understanding of [gap] in [context]. This limits [consequence]. The present study addresses this problem by [short action].

Example

- Despite widespread adoption of telehealth in primary care, there is limited understanding of how appointment modality affects continuity for multi-morbid patients in urban clinics. This limits service planning and equity monitoring. The present study addresses this problem by comparing continuity metrics across visit types in a large multi-site dataset.

Step 3. Craft a clear aim and SMART objectives

The aim states the overall purpose. Objectives break the aim into specific steps that can be achieved and assessed.

Aim example

- To evaluate the relationship between appointment modality and continuity of care in urban primary care clinics.

Write SMART objectives

- Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound

Objective examples

- Quantify continuity of care across telephone, video, and in-person visits over a 12-month period

- Compare continuity by patient complexity and clinic site

- Identify service factors associated with higher continuity within remote modalities

Step 4. Formulate research questions or hypotheses

Choose the form that matches your design. Qualitative studies often use research questions. Quantitative studies often test hypotheses. Mixed methods may use both.

Good questions are

- Directly aligned with the aim and objectives

- Focused enough to answer with your data and methods

- Written in clear, simple language

Question examples

- How do postgraduate students describe the factors that sustain motivation during online learning

- What service factors are associated with higher continuity within remote modalities

Hypothesis examples

- H1: Patients using video visits will have lower continuity scores than those using in-person visits

- H2: After adjusting for complexity, clinic site will significantly predict continuity

Step 5. Explain the significance and contribution

You now persuade the reader that the study matters. Do not oversell. Be precise about who benefits and how.

Cover two angles where possible

- Academic contribution: fill a defined gap, test or extend a framework, refine a measure

- Practical contribution: inform policy, improve service delivery, support decision making

Quick prompts

- This study contributes to scholarship by [theoretical or empirical contribution].

- This study offers practical value by [policy insight, tool, guideline, benchmark].

Step 6. Define scope and limitations

Set boundaries so expectations are realistic and methods are justified.

Clarify scope

- Population or data source

- Setting and period

- Concepts and variables of interest

Acknowledge limitations honestly

- Sampling constraints or response bias

- Measurement limits or missing data

- Feasibility constraints such as time or access

One-paragraph model

- The study focuses on [population] in [setting] from [timeframe]. It examines [key concepts]. Findings may not generalise to [excluded groups or settings]. Data rely on [source], which may introduce [bias], mitigated through [brief step].

Step 7. Define key terms and concepts

If your topic uses specialised vocabulary or contested concepts, define them up front. Keep definitions short and cite the standard you follow if required by your programme.

When to include this section

- Terms have multiple competing definitions

- You are adapting or operationalising a concept in a specific way

- You are using an index, scale, or coding scheme that is not widely known in your field

Tip

- Prefer recognised definitions from authoritative sources. Then explain your operational definition that links the concept to your data.

Style and Voice: What Examiners Expect

Write with clarity and calm authority. Your reader should feel guided, not overwhelmed.

- Use precise verbs such as examine, evaluate, compare, explore

- Keep paragraphs focused, each with a single controlling idea

- Use transitions that signal logic, such as therefore, however, in contrast, as a result

- Avoid filler phrases and rhetorical questions that do not add substance

- Maintain consistency in tense and person

Common Mistakes and How to Fix Them

Mistake: Turning the introduction into a literature review

Fix: Keep the background selective. Save detailed synthesis for the literature review. Two or three big-picture citations are enough in this chapter.

Mistake: Vague problem statement

Fix: Name the gap, context, and consequence. Use the three-move structure: what we know, what we do not know, why that matters.

Mistake: Aims and objectives that do not align

Fix: Test each objective against the aim. If an objective does not help achieve the aim, remove or reword it.

Mistake: Questions that cannot be answered with available data

Fix: Rewrite questions so they match your dataset, access, and timeframe.

Mistake: Overpromising impact

Fix: Be precise about contribution. Replace broad claims with concrete, credible outcomes.

Quality Checklist Before You Submit

- The background orients without duplicating a literature review

- The problem statement names a clear gap with a tangible consequence

- The aim is one sentence and the objectives are SMART

- Questions or hypotheses align with the objectives and are answerable

- The significance shows both academic and practical value where appropriate

- Scope and limitations are explicit and proportionate

- Key terms are defined where ambiguity could arise

- Tone is clear, concise, and confident, with smooth transitions