How to Write an Abstract in a Dissertation: A Practical Guide for PhD Students

Writing an abstract for a dissertation is deceptively challenging. At first glance, it appears to be a straightforward summary—but in truth, it requires the skill of condensing your entire research project into a concise, coherent, and standalone piece of academic writing. For PhD students, the stakes are even higher: the abstract is often the first section your examiners, future employers, or indexing databases will read. It must therefore deliver clarity, precision, and authority within a tight word limit—typically 200 to 350 words.

If you’re feeling stuck, overwhelmed, or unsure of how to begin, you’re not alone. Many doctoral candidates find abstract writing difficult precisely because it demands both deep knowledge and absolute conciseness. This guide breaks down the process step-by-step and offers insight into what examiners really expect from a high-quality dissertation abstract.

Discover our complete dissertation guide series: [Abstract], [Introduction], [Literature Review], [Methodology], [Results], [Conclusion], [Discussion], [References], and [Appendix].

What Is the Purpose of a Dissertation Abstract?

The abstract serves several important functions:

- Provides a standalone overview of your research, allowing others to quickly grasp the nature and scope of your study without reading the full thesis.

- Appears in institutional repositories and academic databases, meaning it influences how your work is discovered, cited, or referenced by future scholars.

- Guides your examiners’ initial impression, which can affect their expectations before they begin reading your dissertation in full.

For this reason, your abstract must be more than a formality—it should be a carefully written academic product in its own right.

What to Include in Your Abstract: Essential Elements

A high-quality dissertation abstract typically includes the following five elements. These are not written as bullet points in the final version but are essential building blocks that should appear in natural, flowing academic prose:

- Research problem and context: Begin by briefly introducing the scholarly or real-world problem your study addresses. What gap, issue, or unresolved question does your dissertation seek to investigate?

- Aim and objectives of the study: Clearly state what the dissertation sets out to achieve. Your central research aim, along with specific objectives or hypotheses, should be evident.

- Methodology: Outline the approach you took. What kind of data did you collect? What research design did you use? Quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods? The reader should understand how your findings were generated.

- Key findings: Present your most important results. Avoid overwhelming the reader with too much detail or too many numbers—focus on core patterns, significant effects, or emergent themes.

- Conclusion and significance: Explain what your findings mean. What is the broader implication of your work? Does it support, challenge, or extend existing knowledge? How does it contribute to your field?

Each of these should be delivered in no more than 1–2 sentences, forming a tight, unified narrative that captures your research from start to finish.

How to Structure the Dissertation Abstract

Your abstract should follow a logical flow from problem to outcome. Here’s a standard structure that works across disciplines:

Opening sentence: Set the stage with 1–2 lines on the research topic and context.

Research aim: State what the dissertation aimed to explore or resolve.

Methods: Briefly explain your methodology, including sample, data collection, and analysis.

Findings: Highlight your core results. Use numbers if appropriate, but don’t go into detail.

Conclusions: Summarise what the results mean and why they matter.

Contribution: End with a note on originality or implications for future work.

Keep paragraphs short and focus on clarity over style.

Our Full-Service Support for PhD Researchers

Tips for Writing a Strong Abstract

If you’re struggling to draft or revise your abstract, here are proven academic strategies that can help you sharpen your writing and improve clarity:

- Write the abstract last, not first: Many students attempt to write their abstract too early. Since your abstract must reflect your final structure, arguments, and findings, it is best written after the rest of the dissertation is complete.

- Think like your examiner: Ask yourself: If I were reading only this abstract, would I understand the essence of the research? Would I be able to explain what the study was about, how it was done, and why it matters?

- Avoid vague or inflated language: Phrases like “This study explores the important topic of…” or “The findings may potentially revolutionise…” are red flags. Keep your tone academic, modest, and evidence-based.

- Avoid literature references: Your abstract should stand alone. Do not cite other authors or refer to literature. The focus is your work—nothing else.

- Don’t replicate your introduction: The abstract is not a shortened version of the introduction. It must summarise the whole study, not just the background or rationale.

- Use keywords strategically: Consider which terms future researchers might search when looking for work like yours. Embedding relevant, discipline-specific terms increases discoverability.

- Check formatting and word limits: Adhere to your university’s formatting guidelines. Abstracts are typically limited to a maximum of 300–350 words, though some institutions may require fewer.

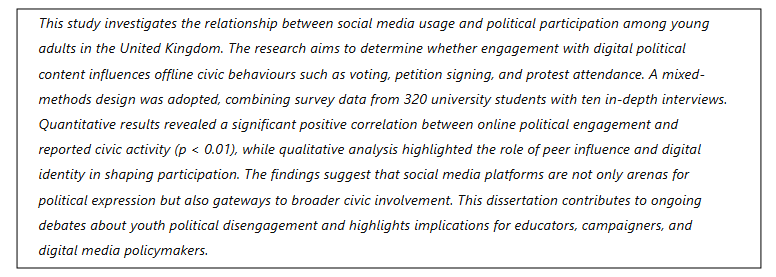

Example: Dissertation Abstract (Social Sciences)

This example illustrates how each element is integrated into a coherent abstract:

This abstract is:

- Self-contained

- Concise

- Methodologically clear

- Focused on specific results and implications

- Free from jargon and vague phrasing

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Even strong dissertations can be undermined by weak abstracts. Be aware of the following pitfalls:

- Writing too generally: Statements like “This study explores education” say very little. Be specific about your topic, method, and population.

- Ignoring results: Some students write abstracts that describe the process of research but don’t mention any findings. This makes the abstract incomplete.

- Overloading with detail: While specificity is important, listing every variable, percentage, or p-value will overwhelm the reader.

- Failing to connect findings to impact: Your conclusion should offer at least one sentence on the so what—why the research matters or what it contributes.